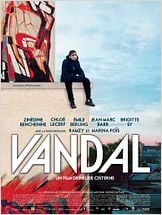

February 4 to 8 marks the Hip Hop Art’Mature Festival at Issy-les-Moulineaux, just south of Paris. Among the many activities scheduled this week, including sketch competitions, beatmaking, and dance performances, was the screening of Hélier Cisterne’s 2013 film, Vandal. Vandal is a coming of age film that explores adolescence, love, and graffiti, situated in Strasbourg. Following Chérif, a youth who is sent to live with his aunt and uncle after an escapade with a stolen car. Part of this move was to avoid jail, instead, Chérif is charged with searching for a stage, an internship. In Strasbourg, he works in construction, first through a preparatory class, and then with his father, who lives in Strasbourg with his new partner.

Chérif, played by Zinedine Bechenine, is hard to read, but even harder to understand. He says little, and communicates with hunched shoulders, a furrowed brow, and pursed lips. Picked on by another stagière he gets into fights but refuses to tell his side of the story. Most of his interactions with adults involve him being yelled at, while he withholds explanations. It turns out that Chérif’s studious, well-behaved cousin, Thomas, is a graffiti writer. Thomas brings Chérif into his crew, ORK, initially as a lookout. In one of the most visually arresting scenes in the film ORK bomb an underpass, backlit by highway lights, which cast their shadows against the wall so that they are part of the painting, a quiet, industrial dance of ghosts, animated by the breath-like sound of aerosol can valves. Thomas introduces Chérif to a nocturnal world of expression where conversations play out on rooftops, under bridges, and alongside train cars, intense and uncensored, beneath and outside the reach of adult and bourgeois sensibilities. We also witness a conflict between the bombing style of ORK, and the Siqueiros-like expressionism of another writer, Vandal, whose art work is executed by real-world graffiti artist Lokiss.

While developing as a writer, Chérif becomes romantically involved with his classmate, Elodie, a young woman who (partially) saves him from being jumped and has a fraught relationship with an older brother who is in a gang. Trying to find a place to be alone, Chérif brings Elodie to ORK’s secret spot. While painting her leg he is discovered by the crew, and violently ejected from the group, and the world to which he finally has a sense of belonging. Now alone, he follows Vandal, tracking his movements, and using his intelligence to gain entry back into ORK. In a climactic scene, they chase Vandal on a train track, causing him to climb on top of a train where he is electrocuted by the wire overhead.

The rest of the film involves Chérif negotiating his guilt in Vandal’s death, and his sense of responsibility to continue Vandal’s legacy: he takes on his name, and explores his hiding place, ultimately following the same trajectory up a construction scaffolding on a partially completed building that Vandal has taped in a youtube video, and then writing Vandal’s name in a simple yet intense burner.

Assistant scenographer, Nicolas Journet, explained after the screening, that the film is indeed a coming of age film, but that its conclusion does not offer a clear answer as to the direction that the young protagonist’s life will take– rather, it only points to the necessity, the emotional and psychological imperative for expression— that Chérif carries out in taking up and continuing Vandal’s legacy. Graffiti as a narrative device suggests to viewers that it is not the end that is important, but the process, the investment in creation for its own sake.

The production process of the film is fascinating in itself. As mentioned above, Lokiss does the graffiti for Vandal, his work can be found on youtube, and has been involved in the French graffiti scene from its earliest years. The graffiti for ORK is also done by a crew, and represents a more bomber-style form of graffiti, concerned more with plurality than perfection. The film puts into play these dual (and sometimes competing, but also intimately related) tendencies in graffiti culture between repetition and the unique, the need to get up, and the desire for distinction. Moreover, many of the art created for the film is gone, becoming part of graffities legacy as art ephemère, ephemeral. The film takes graffiti and plays with and even modifies dominant tropes, replacing hip hop music, in key scenes, with classical music, notably for those involving Vandal himself, or Chérif echoing his work.

An ethos of openness informed some of the filming, what Journet described as the “magic” of cinema. For instance, in the scene where ORK paints by highway light, their shadows becoming part of the mural, such an aesthetic effect was purely accidental. Such openness was also enabled by the disposition of funders and some of the structures of the French film industry, where subsidization enables filmmakers to pursue aesthetic, cultural, and political interests that may not coincide with the imperatives of the market. However, the film was not fully outside the constraints enforced on graffiti by state and property: some of the struggles in making the film, Journet remarked, mirror the struggles in being a graffiti writer. Crucially, the scene of Vandal’s electrocution was not filmed on the SNCF, France’s major rail line. SNCF refused to allow filming, partially due to safety concerns, and partially because of the politics (and pejoratives) surrounding graffiti culture. Instead, all train scenes took place on a private line in Strasbourg.

As part of a growing genre, or lineage of graffiti fiction films, used to explore themes of adolescence, love, and belonging, Vandal offers a compelling mediation on what it is to express without communicating, and the cathartic work that writing may do for troubled writers. I must admit that I was profoundly moved by Bechenine’s depiction, or channeling, the opacity of a particular kind of adolescent masculinity in revolt, certainly not legible to others, but also not fully intelligible to itself, where the call for explanations, or reason, only reinforces isolation and skepticism if not outright suffering in the face of yet more talk. My younger brother had a tumultuous high school career, one marked by ill thought out escapades, but also, more consistently, dead end arguments in our house that called for reason but more often ended in slammed doors. Watching Chérif’s struggle with crushing guilt, one that is unrecognizable as a struggle, and instead mere rancour by his elders, made me wonder what I was missing in my demands for reason and responsibility years ago, but also, what structures can be created in educational systems and family networks that allow for expression without full communication, allowing youth in distress to meditate and incubate.

Moreover, the film points to a less-explored phenomenon of suburban or quasi-urban graffiti, as well as graffiti (and hip hop’s) circulation from the United States to Europe. Moreover, it is the product of a urban art milieu where circulation (not only physically, but now, digitally) becomes increasingly critical: although graffiti continues to be an ephemeral art based on traces, its digitality echoes the haunting quality that tags and pieces engender– they have afterlives beyond that of their makers.

In any case, it offers a thoughtful and emotionally provocative meditation on what it is to find a form of self-expression that does not offer escape from structures of misunderstanding or abrasion, but a more humble but no less powerful tactic of persistence, creation, and holding in reserve, surviving such processes.